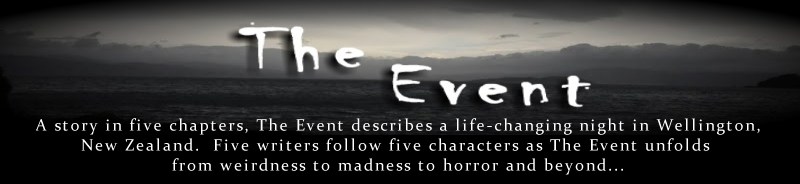

The Event is a collaboration between five Wellington writers. In five sections The Event explores a life changing night in Wellington, New Zealand and its consequences for five Wellingtonians. From simmering menace to face-melting horror The Event spirals into chaos and destruction.

Wellington will never be the same again.

CAST

Seth is a student, a dreamer, and a partier. Coping with a hangover is hard enough at the best of times, but when the world he knows begins to slip away Seth questions whether he can trust his own senses or whether he is becoming a monster.

Michelle wishes her life were more like a movie. It should be moving and emotional, its message should be clear. Instead she must pass through life's pale shadow of Hollywood's manufactured dreams. As life slips inexorably into the stuff of horror films, will she finally begin to really feel?

Margaret hurts. People are so rude, they can't let things go, can't let her be even for a second. She has to live with the pain of her cumbersome, misshapen leg and the cruelty of people who don't understand...

Adam yearns for something interesting to happen, some excitement to brighten his days. He also wishes he had the confidence to talk to the cute girl he buys coffee from every morning. In the chaos, confusion and crisis of The Event will Adam find the strength to take action?

Robin loves being an aunt, even if her sister does give her a hard time about sorting her life out. Rescuing a suicidal stranger and witnessing inexplicable events takes its toll on Robin and when disaster strikes she finds herself alone...

Saturday, November 20, 2010

Thursday, November 19, 2009

Part Five - Robin

At the height of Mt Victoria, the creature reached towards the sky. Robin walked under its arching limbs, already overgrown with vines; she had people to meet. At the bright pyramid of the Byrd Memorial she found them, and smiled shyly. “You made it,” she said.

Out of the ... branches? overhead, two small faces peered at her. At her side, Robot waved cheerfully and started to climb up to them. Still at ground level, Robin patted the bundle tied to her chest and nodded at their keeper. “How are they doing?”

“Oh, you know, still having nightmares. Not so many this past couple of weeks.” He rubbed a hand over his spiky hair. “Can’t blame, ‘em. I haven’t had a drink in three months, eh?”

“Yeah,” Robin said. “I know what you mean.”

Life had changed a lot in the last three months. The rebuilding was still going on – from the top of this hill she could see the grey concrete remains of poor dead Wellington, the bit in the centre that had collapsed in on itself. The bulldozers had moved in, but she wasn’t sure if anyone was going to move back in there. The hills were safer. The hills were home.

And the other rebuilding was going on, too, as people found their families again, or made new ones. Robot had turned up, of course, and Aroha even, hypothermic and shivering, had been found in the old Manners Mall two days after It happened, and been cracked out of hospital a month later. She had thought that Christie and Alex were gone for good, but no, even they had been alright, come back from their castle in the clouds and in the care, inexplicably, of a guy she’d used to go out with. They’d been pleased to see her, but hadn’t wanted to come home with her.

Seth was, at any rate, a decent guy at heart, for all his leather jackets and nose rings. Robin had been giving him maintenance money and tried not to feel like a divorced parent. She looked through the creature’s high arms at her kids, and waved at them. “Christie and Alex talking yet?” she asked.

Seth shook his head, “Nup.” He ran his hand over his hair again. “But I think they talk to each other. With their brains or something. They always seem to know what the other one is up to. I dunno.”

She nodded. “You sure you’re OK with Robot for the afternoon?”

“Yeah, yeah.”

“Cool, I’ll meet you two up here around 6 then.” She gave him a wad of money and kissed him, awkwardly, on the cheek. “Thanks.” And she walked away from her kids, and the Creature – Tane Mahuta some people were calling it – and picked her way down the tracks of Mt Vic. She and Aroha had someone else to see.

***

The Other Creature, the one of the sea, had remained in the harbour, although it had sagged greatly, to her sorrow. There was a part of her that missed that night, when she could hear the great music. When she got to Oriental Beach she took her shoes off and wiggled her toes in the coarse sand, and unhitched Aroha from her sling. Behind her, she heard someone walking and turned quickly. They’d shot one of the crazies last week, but there were still some around she’d heard.

It was just a man, though, without that wild look the crazies had. He was wearing a gaudy Hawaiian shirt and shirts, and seemed awfully familiar.

“Do we know each other?” he asked.

“I don’t –” Robin hefted Aroha onto her lap, “yes, maybe we do...?”

He grinned at her suddenly. “It was you. You pulled me out of the water that day.”

She shook her head at him. “Wait. Noel? You look so different. Relaxed. Happy.”

He nodded at her and sat down next to her. “Making that coding deadline just doesn’t seem that important anymore.”

Robin nodded and lay back into the sand to look at the sky. They sat there for a while, the three of them, under the blue sky, at the boundary of earth and water, sea and air. Then she got up and finished taking her clothes off, and Aroha’s, and said good bye to Noel. “Take care of yourself, hey?”

“Yeah, see you around” he said, as she walked into the sea.

It was funny, Robin thought, that there were people who had left Wellington. She’d heard about them in the newspapers, or local gossip, someone’s friend or rellie who’d gone away with the evac and never come back. She’d thought they were nuts, crazier than the crazies. It wasn’t even that they’d given up, it’s that they’d left a place that was real. Nowhere had been realer than Wellington even before the Event, and now, now it was the Marriage of Sea and Sky. How could anyone leave that behind them? She was waist deep and put Aroha into the water to paddle next to her.

Then, of course, there were the people who had never gone away, or rushed back from the evac camps as soon as they could manage it. Mostly people were living up in the hills, but they could still come down to visit the sea, and the Other One, and the graves of the people they’d lost. Realer than real. She dived down into the water, feeling the coolness slide down her hair, the sweet water fill her lungs. She rolled over to look at the boundary of water and air above her, and little Aroha paddling along. She reached up a hand to tickle her round belly, and the little girl giggled and dived down to join her, flipper feet whirring away like a duck’s legs.

They went deeper and swam away to pay their respects to the Other One, the One which had not survived the night. But in all that chaos and destruction it had tried to be born, and that was a noble thing, as alien as it was.

Aroha looked at her with round, wise eyes, her little water baby. It was enough.

Out of the ... branches? overhead, two small faces peered at her. At her side, Robot waved cheerfully and started to climb up to them. Still at ground level, Robin patted the bundle tied to her chest and nodded at their keeper. “How are they doing?”

“Oh, you know, still having nightmares. Not so many this past couple of weeks.” He rubbed a hand over his spiky hair. “Can’t blame, ‘em. I haven’t had a drink in three months, eh?”

“Yeah,” Robin said. “I know what you mean.”

Life had changed a lot in the last three months. The rebuilding was still going on – from the top of this hill she could see the grey concrete remains of poor dead Wellington, the bit in the centre that had collapsed in on itself. The bulldozers had moved in, but she wasn’t sure if anyone was going to move back in there. The hills were safer. The hills were home.

And the other rebuilding was going on, too, as people found their families again, or made new ones. Robot had turned up, of course, and Aroha even, hypothermic and shivering, had been found in the old Manners Mall two days after It happened, and been cracked out of hospital a month later. She had thought that Christie and Alex were gone for good, but no, even they had been alright, come back from their castle in the clouds and in the care, inexplicably, of a guy she’d used to go out with. They’d been pleased to see her, but hadn’t wanted to come home with her.

Seth was, at any rate, a decent guy at heart, for all his leather jackets and nose rings. Robin had been giving him maintenance money and tried not to feel like a divorced parent. She looked through the creature’s high arms at her kids, and waved at them. “Christie and Alex talking yet?” she asked.

Seth shook his head, “Nup.” He ran his hand over his hair again. “But I think they talk to each other. With their brains or something. They always seem to know what the other one is up to. I dunno.”

She nodded. “You sure you’re OK with Robot for the afternoon?”

“Yeah, yeah.”

“Cool, I’ll meet you two up here around 6 then.” She gave him a wad of money and kissed him, awkwardly, on the cheek. “Thanks.” And she walked away from her kids, and the Creature – Tane Mahuta some people were calling it – and picked her way down the tracks of Mt Vic. She and Aroha had someone else to see.

***

The Other Creature, the one of the sea, had remained in the harbour, although it had sagged greatly, to her sorrow. There was a part of her that missed that night, when she could hear the great music. When she got to Oriental Beach she took her shoes off and wiggled her toes in the coarse sand, and unhitched Aroha from her sling. Behind her, she heard someone walking and turned quickly. They’d shot one of the crazies last week, but there were still some around she’d heard.

It was just a man, though, without that wild look the crazies had. He was wearing a gaudy Hawaiian shirt and shirts, and seemed awfully familiar.

“Do we know each other?” he asked.

“I don’t –” Robin hefted Aroha onto her lap, “yes, maybe we do...?”

He grinned at her suddenly. “It was you. You pulled me out of the water that day.”

She shook her head at him. “Wait. Noel? You look so different. Relaxed. Happy.”

He nodded at her and sat down next to her. “Making that coding deadline just doesn’t seem that important anymore.”

Robin nodded and lay back into the sand to look at the sky. They sat there for a while, the three of them, under the blue sky, at the boundary of earth and water, sea and air. Then she got up and finished taking her clothes off, and Aroha’s, and said good bye to Noel. “Take care of yourself, hey?”

“Yeah, see you around” he said, as she walked into the sea.

It was funny, Robin thought, that there were people who had left Wellington. She’d heard about them in the newspapers, or local gossip, someone’s friend or rellie who’d gone away with the evac and never come back. She’d thought they were nuts, crazier than the crazies. It wasn’t even that they’d given up, it’s that they’d left a place that was real. Nowhere had been realer than Wellington even before the Event, and now, now it was the Marriage of Sea and Sky. How could anyone leave that behind them? She was waist deep and put Aroha into the water to paddle next to her.

Then, of course, there were the people who had never gone away, or rushed back from the evac camps as soon as they could manage it. Mostly people were living up in the hills, but they could still come down to visit the sea, and the Other One, and the graves of the people they’d lost. Realer than real. She dived down into the water, feeling the coolness slide down her hair, the sweet water fill her lungs. She rolled over to look at the boundary of water and air above her, and little Aroha paddling along. She reached up a hand to tickle her round belly, and the little girl giggled and dived down to join her, flipper feet whirring away like a duck’s legs.

They went deeper and swam away to pay their respects to the Other One, the One which had not survived the night. But in all that chaos and destruction it had tried to be born, and that was a noble thing, as alien as it was.

Aroha looked at her with round, wise eyes, her little water baby. It was enough.

Wednesday, November 4, 2009

Part Five - Margaret

‘We found her like this,’ said the soldier. Well. Not quite a soldier. A sergeant in the territorials. ‘Walking around, just like this. Almost shot her.’

The doctor, a junior house surgeon about the same age, looked at the man with tired disapproval.

‘Were those your orders, to shoot people?’

The sergeant shrugged.

‘Fucken look at her. Looks like a zombie.’

He wandered off. A short while later, the doctor saw he’d joined a game of touch with the rest of his company.

The woman kept staggering back onto her feet in triage. A ghastly sight, given the condition of her jawbone (it had come loose from one side of her face). They helped her down, pushed her down onto the bench. ‘What’s your name?’ they’d asked her. Eventually one nurse had the idea of tying her down with a bedsheet, and much later a sedative was administered. It wasn’t until the next morning they had time to disinfect her wounds, or to operate on the jaw.

Nicola Rutlidge barely recognised her life anymore. For instance: it was Friday night. Two weeks ago she would have been out on the dancefloor at Coyote with her friends, all of them nursing students like her. Dancing, shouting, occasionally letting the right boys break into their circle.

That was, obviously, before all of this. Before the Big Fucking Disaster, before the camp out here in Kilbirnie. Camp Eight, it was called.

Before David Handscombe. Doctor Dreamboat.

She had another shift with him today – a night shift. “Humana-humana,” as Becca would have said. She took time getting ready in the quarters, which two weeks ago would have been a principal’s office. Leaned in close against the mirror. Not that there was much she could do, there were like no cosmetics anywhere. She picked at a blackhead on her nose, straightened her eyebrows. Smiled, then smiled a different way which brought out her dimples. She wondered briefly if any of her friends had died last week.

‘Hurry up, I need the mirror too.’

‘Piss off.’

The dimples would have to do. A natural asset. Someone had once said that she looked like Katie Holmes when she smiled.

Nicola found she was thinking a lot about her grandparents these days. About the War, how Gran had been a typist in London, and Grandad had been her boss (lucky old Grandad, a boss in a city without men). They’d gotten talking over a man in their office they’d thought was a spy. Could something like that be happening to her? It drove her nuts just thinking about it. “Mrs David Handscombe”.

It would be just too much. But then that’s what happened in a crisis, people got driven together. Like a movie or something.

It was getting dark as she walked beside the sports field. Kids playing, people moping around, talking and smoking. She’d need an “in”, something to talk about. Better yet, some reason to get him alone. She walked into C Ward, which two weeks ago would have been an assembly hall – C Ward was the ones who weren’t going to make it. At least most of them wouldn’t. It made you sad when you thought about it, all the mums and dads and kids. And the crazy old bitch in bed 8, the one who stared back at you.

She remembered a time two days ago when they’d stripped her and washed her. Remembered the pink streak of knotted tissue running down her leg.

The other doctor had stepped back in alarm. ‘Infected,’ he’d said.

But David had pushed him aside, had looked so much like Guy Warner as he took a closer look. ‘I don’t think so mate. Look.’ Pointing at something. ‘Look at the bones. That’s an old scar.’

He’d even spoken to her. ‘Have you had an operation on your hip? As a child? Did you have an operation here?’ So cool. You could tell the old cow wasn’t even listening, but he still had the courtesy to ask her.

Afterwards, when they were walking back together, he’d said: ‘Those bones are so strange, I’m almost tempted to think...’

Nicola had turned to him.

Had breathlessly asked: ‘Think what?’

David, her David had blushed, and said: “You sometimes see that on Siamese twins. She... ah, the woman has two legs, but they’re both the left. One of the legs might have belonged to her sister.”

So much like a soap opera. He was so fucken hot.

Nicola stared at the woman now, who of course said nothing, she never talked. Just looked back at you with dead eyes, like a fish on a bed of ice. A fish with a wire brace on its bandaged jaw. Around them people gasped and moaned and cried out in pain, but this one never made a sound.

‘What are you looking at, Lefty?’

And she almost jumped out of her skin, because the old girl lifted her arms up from under the sheets, held them there for a second, then put her hands against the sides of her head. Covering her ears. Which was scary enough, sort of, but also Nicola noticed there were grey patches all over the wrinkly flesh of her forearms.

So that was it. That was the “in”.

It took her almost two hours to find her chance.

‘Where’s Dr Handscombe?’

‘He’s out somewhere. They’re delivering supplies.’

Waiting, waiting. Then when he came in they were receiving new patients, and one of them had a badly infected foot so they’d had to roll him into theatre and remove it. Finally over the sinks, Nicola saw her chance.

‘Doctor,’ she said to him.

‘Yeah.’ He looked so sad. Poor sad puppy.

‘I’m worried about that patient in C Ward. You know, bed 8.’

David looked at her, she could tell he was drawing a blank.

‘The, uh, Siamese case,’ she added, with awkward emphasis and a dimpled smile.

‘Oh,’ he said. ‘What do you mean, what’s the matter?’

‘She’s... well I don’t know, and I’d like your opinion. But I think I’ve found traces of infection on her arms.’ A careful, dramatic pause. ‘They might have to go.’

He sighed. ‘Okay, give me a minute.’ And a minute had been half an hour, but finally he’d appeared and given her an electric pat on her shoulder. ‘Let’s go take a look.’

But when they’d walked down through C Ward, 8 was empty. The covers pulled out and spilled across the ward like a white linen wound.

The old bitch had gone, had danced away on her two left feet.

Early Saturday morning it rained. All along Evan’s bay, a hard grey mist.

There was a check point by the lighthouse, concrete blocks pulled out to stop traffic, but no-one there. Just sand bags, boxes of supplies. So she’d walked on through.

Such sights, downtown. Such amazing sights. And the bulldozers and cranes trying to put it all back together again. Parked vans with flashing lights. Voices calling out to her – no, no. Hands over the ears. No more time to listen to them now.

Out in the harbour – if you looked you could see pieces of it sticking out, like one of those sculptures they put around town. Just another thing that didn’t mean anything. And on the hill behind her, something tall and beautiful, another useless bit of modern art.

Nothing in the sky though. It was vast and grey, with nary a word to say to anyone.

At the Cenotaph they had water blasters, there were three of them cleaning the pavement. One of them saw her, froze like a deer in headlights, but all she was there to do was walk up to the metal pole (it was there, exactly where she’d lost it), snatch it up, and walk on.

Strange how she couldn’t remember her own name, or anything of her life from before, but she’d known exactly where to find that pole. The big round base clunked against the footpath as she made her way uphill, clunked with a dull echo as she walked beneath the overhanging motorway.

She thought a lot about the voice. Tried to remember it, things it had said to her. But the love and the heat had gone for good, and afterwards only the effects remained. Only the lessons it had taught her.

‘Ma,’ she said, clunking up this long, leafy street. What was this street called? Those were the Gardens, over there.

‘Ga,’ she said. Tired from a steep climb, leaning against the pole for a moment and watching a queer old building that may once have been a fire station.

‘Ret,’ she said. That sounded about right. These shops looked familiar. The chip shop run by that Chinese couple. Closed of course. No chips today. Oh don’t think about food – she didn’t care if she never ate again. Couldn’t stomach the idea. Too wet, too warm, too red.

So quiet along here. Every now and then a car rolled past. Green recycling bins out on the street – that was funny. And people sorting through them, like furtive little birds picking out treasure for their nests. Worried eyes looking up at her. No, I will not hurt you, you are beneath my notice.

But what about this! All of this greenery. She looked around herself in a daze, it was all around her, all so green and lush. The bushes came down off the hill and straight onto the street, they were so alive, so full of wriggling things which hid and fucked and ate and gave birth to each other, how had she never noticed this before? She knew instinctively that she had come this way often, had never once stopped to appreciate what was happening on the side of this road. How?

Her head had been full of thoughts, of course. Full of cares and worries. Ma-Ga-Ret. That sound represented some sort of pattern, a cage in which she’d sat, patrolled and guarded by an evil jailor, a wicked face looking down at her through the steel bars, grinning and taunting her. But now - nothing above her but a calm grey sky. The voice had come, and now the rain had stopped. So much to be grateful for. Oh well.

There was something she was supposed to do.

She kept walking, wondering at the world around her, but couldn’t work out what it was.

Lucky for her, a car coming the other way stopped beside her.

‘Margaret!?’ said the woman driving the car.

She paused in her walking, looked in through the open window. A face she recognised stared back with mouth hanging open.

‘Oh my God, is that you? Get in the car.’ The driver leaned over, the door popped open.

She shook her head.

‘Are you all right? What happened to you? Your face!’

She said nothing. Peered in through the open door. The woman, so dreadfully familiar, sat behind the controls of the car with one leg protruding from beneath her shapeless floral dress.

‘Margaret. My God.’

There was a sound for this woman. A sound and a pattern and a cage. She remembered it, said it.

‘Sho. Na.’

‘Yes, it’s me. Are you all right? Get in.’

Again she shook her head. The woman stared, made an exasperated motion with her hands, then looked back down the road.

‘Are you heading for the house?’

The correct thing to do would be to nod. She nodded.

‘Can you make it? You look terrible. Listen... I’m going down to the garden centre, you know? They have a station there for food, I have to go and get food. For the kids. Can you walk? Can you make it back to the house?’

Another nod. And a flash of memory – she hated this woman.

‘Craig is at home but he’s sick. I mean, he’s injured, he’s in bed. The kids are there. Are you going to be okay to walk? You sure you don’t want to get in?’

(Shona stared at her. Her sister shook her head. Thin and drawn, dressed in a nightgown with bandages and wire running across her face, stains of old blood seeping through the gauze. Margaret gestured to the pole, as if to say it wouldn’t fit inside the car, or perhaps to demonstrate it would help her walk home.)

‘...Okay. I’ll see you back at the house?’

(Margaret nodded. For fuck's sake, she was always like this - impossible)

‘I’ll be back there in half an hour. Make sure you go straight there. My God, you look terrible. But thank God, I mean, you’re alive. Okay. I’ll see you at the house.’

She watched as the woman, as the despicable creature in the car swung the door shut and used her one leg to manipulate the pedals of the car, an automatic. A “customised Volvo”, that’s right. Little flashes of memory.

“Craig is at home but he’s sick.” Ah yes. Craig. Where is the rent money.

“The kids are there.”

A long moment out there under the grey sky, thinking and remembering. Yes. Craig and the kids. That would be a start. And then the woman would be home in half an hour.

She turned and started walking with a clunk. That was the round base of the metal pole striking the pavement. The pole. She’d rescued it on her way over. Knew there had to be a reason for that. The metal on the base had gone black, sticky and grimy with residue.

Birds singing somewhere nearby. So many things to be grateful for.

The doctor, a junior house surgeon about the same age, looked at the man with tired disapproval.

‘Were those your orders, to shoot people?’

The sergeant shrugged.

‘Fucken look at her. Looks like a zombie.’

He wandered off. A short while later, the doctor saw he’d joined a game of touch with the rest of his company.

The woman kept staggering back onto her feet in triage. A ghastly sight, given the condition of her jawbone (it had come loose from one side of her face). They helped her down, pushed her down onto the bench. ‘What’s your name?’ they’d asked her. Eventually one nurse had the idea of tying her down with a bedsheet, and much later a sedative was administered. It wasn’t until the next morning they had time to disinfect her wounds, or to operate on the jaw.

Nicola Rutlidge barely recognised her life anymore. For instance: it was Friday night. Two weeks ago she would have been out on the dancefloor at Coyote with her friends, all of them nursing students like her. Dancing, shouting, occasionally letting the right boys break into their circle.

That was, obviously, before all of this. Before the Big Fucking Disaster, before the camp out here in Kilbirnie. Camp Eight, it was called.

Before David Handscombe. Doctor Dreamboat.

She had another shift with him today – a night shift. “Humana-humana,” as Becca would have said. She took time getting ready in the quarters, which two weeks ago would have been a principal’s office. Leaned in close against the mirror. Not that there was much she could do, there were like no cosmetics anywhere. She picked at a blackhead on her nose, straightened her eyebrows. Smiled, then smiled a different way which brought out her dimples. She wondered briefly if any of her friends had died last week.

‘Hurry up, I need the mirror too.’

‘Piss off.’

The dimples would have to do. A natural asset. Someone had once said that she looked like Katie Holmes when she smiled.

Nicola found she was thinking a lot about her grandparents these days. About the War, how Gran had been a typist in London, and Grandad had been her boss (lucky old Grandad, a boss in a city without men). They’d gotten talking over a man in their office they’d thought was a spy. Could something like that be happening to her? It drove her nuts just thinking about it. “Mrs David Handscombe”.

It would be just too much. But then that’s what happened in a crisis, people got driven together. Like a movie or something.

It was getting dark as she walked beside the sports field. Kids playing, people moping around, talking and smoking. She’d need an “in”, something to talk about. Better yet, some reason to get him alone. She walked into C Ward, which two weeks ago would have been an assembly hall – C Ward was the ones who weren’t going to make it. At least most of them wouldn’t. It made you sad when you thought about it, all the mums and dads and kids. And the crazy old bitch in bed 8, the one who stared back at you.

She remembered a time two days ago when they’d stripped her and washed her. Remembered the pink streak of knotted tissue running down her leg.

The other doctor had stepped back in alarm. ‘Infected,’ he’d said.

But David had pushed him aside, had looked so much like Guy Warner as he took a closer look. ‘I don’t think so mate. Look.’ Pointing at something. ‘Look at the bones. That’s an old scar.’

He’d even spoken to her. ‘Have you had an operation on your hip? As a child? Did you have an operation here?’ So cool. You could tell the old cow wasn’t even listening, but he still had the courtesy to ask her.

Afterwards, when they were walking back together, he’d said: ‘Those bones are so strange, I’m almost tempted to think...’

Nicola had turned to him.

Had breathlessly asked: ‘Think what?’

David, her David had blushed, and said: “You sometimes see that on Siamese twins. She... ah, the woman has two legs, but they’re both the left. One of the legs might have belonged to her sister.”

So much like a soap opera. He was so fucken hot.

Nicola stared at the woman now, who of course said nothing, she never talked. Just looked back at you with dead eyes, like a fish on a bed of ice. A fish with a wire brace on its bandaged jaw. Around them people gasped and moaned and cried out in pain, but this one never made a sound.

‘What are you looking at, Lefty?’

And she almost jumped out of her skin, because the old girl lifted her arms up from under the sheets, held them there for a second, then put her hands against the sides of her head. Covering her ears. Which was scary enough, sort of, but also Nicola noticed there were grey patches all over the wrinkly flesh of her forearms.

So that was it. That was the “in”.

It took her almost two hours to find her chance.

‘Where’s Dr Handscombe?’

‘He’s out somewhere. They’re delivering supplies.’

Waiting, waiting. Then when he came in they were receiving new patients, and one of them had a badly infected foot so they’d had to roll him into theatre and remove it. Finally over the sinks, Nicola saw her chance.

‘Doctor,’ she said to him.

‘Yeah.’ He looked so sad. Poor sad puppy.

‘I’m worried about that patient in C Ward. You know, bed 8.’

David looked at her, she could tell he was drawing a blank.

‘The, uh, Siamese case,’ she added, with awkward emphasis and a dimpled smile.

‘Oh,’ he said. ‘What do you mean, what’s the matter?’

‘She’s... well I don’t know, and I’d like your opinion. But I think I’ve found traces of infection on her arms.’ A careful, dramatic pause. ‘They might have to go.’

He sighed. ‘Okay, give me a minute.’ And a minute had been half an hour, but finally he’d appeared and given her an electric pat on her shoulder. ‘Let’s go take a look.’

But when they’d walked down through C Ward, 8 was empty. The covers pulled out and spilled across the ward like a white linen wound.

The old bitch had gone, had danced away on her two left feet.

Early Saturday morning it rained. All along Evan’s bay, a hard grey mist.

There was a check point by the lighthouse, concrete blocks pulled out to stop traffic, but no-one there. Just sand bags, boxes of supplies. So she’d walked on through.

Such sights, downtown. Such amazing sights. And the bulldozers and cranes trying to put it all back together again. Parked vans with flashing lights. Voices calling out to her – no, no. Hands over the ears. No more time to listen to them now.

Out in the harbour – if you looked you could see pieces of it sticking out, like one of those sculptures they put around town. Just another thing that didn’t mean anything. And on the hill behind her, something tall and beautiful, another useless bit of modern art.

Nothing in the sky though. It was vast and grey, with nary a word to say to anyone.

At the Cenotaph they had water blasters, there were three of them cleaning the pavement. One of them saw her, froze like a deer in headlights, but all she was there to do was walk up to the metal pole (it was there, exactly where she’d lost it), snatch it up, and walk on.

Strange how she couldn’t remember her own name, or anything of her life from before, but she’d known exactly where to find that pole. The big round base clunked against the footpath as she made her way uphill, clunked with a dull echo as she walked beneath the overhanging motorway.

She thought a lot about the voice. Tried to remember it, things it had said to her. But the love and the heat had gone for good, and afterwards only the effects remained. Only the lessons it had taught her.

‘Ma,’ she said, clunking up this long, leafy street. What was this street called? Those were the Gardens, over there.

‘Ga,’ she said. Tired from a steep climb, leaning against the pole for a moment and watching a queer old building that may once have been a fire station.

‘Ret,’ she said. That sounded about right. These shops looked familiar. The chip shop run by that Chinese couple. Closed of course. No chips today. Oh don’t think about food – she didn’t care if she never ate again. Couldn’t stomach the idea. Too wet, too warm, too red.

So quiet along here. Every now and then a car rolled past. Green recycling bins out on the street – that was funny. And people sorting through them, like furtive little birds picking out treasure for their nests. Worried eyes looking up at her. No, I will not hurt you, you are beneath my notice.

But what about this! All of this greenery. She looked around herself in a daze, it was all around her, all so green and lush. The bushes came down off the hill and straight onto the street, they were so alive, so full of wriggling things which hid and fucked and ate and gave birth to each other, how had she never noticed this before? She knew instinctively that she had come this way often, had never once stopped to appreciate what was happening on the side of this road. How?

Her head had been full of thoughts, of course. Full of cares and worries. Ma-Ga-Ret. That sound represented some sort of pattern, a cage in which she’d sat, patrolled and guarded by an evil jailor, a wicked face looking down at her through the steel bars, grinning and taunting her. But now - nothing above her but a calm grey sky. The voice had come, and now the rain had stopped. So much to be grateful for. Oh well.

There was something she was supposed to do.

She kept walking, wondering at the world around her, but couldn’t work out what it was.

Lucky for her, a car coming the other way stopped beside her.

‘Margaret!?’ said the woman driving the car.

She paused in her walking, looked in through the open window. A face she recognised stared back with mouth hanging open.

‘Oh my God, is that you? Get in the car.’ The driver leaned over, the door popped open.

She shook her head.

‘Are you all right? What happened to you? Your face!’

She said nothing. Peered in through the open door. The woman, so dreadfully familiar, sat behind the controls of the car with one leg protruding from beneath her shapeless floral dress.

‘Margaret. My God.’

There was a sound for this woman. A sound and a pattern and a cage. She remembered it, said it.

‘Sho. Na.’

‘Yes, it’s me. Are you all right? Get in.’

Again she shook her head. The woman stared, made an exasperated motion with her hands, then looked back down the road.

‘Are you heading for the house?’

The correct thing to do would be to nod. She nodded.

‘Can you make it? You look terrible. Listen... I’m going down to the garden centre, you know? They have a station there for food, I have to go and get food. For the kids. Can you walk? Can you make it back to the house?’

Another nod. And a flash of memory – she hated this woman.

‘Craig is at home but he’s sick. I mean, he’s injured, he’s in bed. The kids are there. Are you going to be okay to walk? You sure you don’t want to get in?’

(Shona stared at her. Her sister shook her head. Thin and drawn, dressed in a nightgown with bandages and wire running across her face, stains of old blood seeping through the gauze. Margaret gestured to the pole, as if to say it wouldn’t fit inside the car, or perhaps to demonstrate it would help her walk home.)

‘...Okay. I’ll see you back at the house?’

(Margaret nodded. For fuck's sake, she was always like this - impossible)

‘I’ll be back there in half an hour. Make sure you go straight there. My God, you look terrible. But thank God, I mean, you’re alive. Okay. I’ll see you at the house.’

She watched as the woman, as the despicable creature in the car swung the door shut and used her one leg to manipulate the pedals of the car, an automatic. A “customised Volvo”, that’s right. Little flashes of memory.

“Craig is at home but he’s sick.” Ah yes. Craig. Where is the rent money.

“The kids are there.”

A long moment out there under the grey sky, thinking and remembering. Yes. Craig and the kids. That would be a start. And then the woman would be home in half an hour.

She turned and started walking with a clunk. That was the round base of the metal pole striking the pavement. The pole. She’d rescued it on her way over. Knew there had to be a reason for that. The metal on the base had gone black, sticky and grimy with residue.

Birds singing somewhere nearby. So many things to be grateful for.

Sunday, November 1, 2009

Part Five - Seth

Seth was enjoying being a father. If he’d only had himself to look after he doubted he would have held onto sanity at all. Having kids was a lot like owning a pet or having a job. He was required to be certain places and provide certain comforts, regardless of whether he wanted to or felt capable. That regimented activity was forcing him to keep his fingernails dug in to the edge of reason, forcing him not to let go and fall in the abyss.

The kids didn’t talk and that was OK. They barely blinked but he could ignore that. They would spend hours staring at the ocean from the safety of the hills, and that was something he shared with them. When it grew dark and the panic started rising inside him Seth could usher the children back into his hilltop apartment, switch on every light, huddle close with them and listen to the sounds of helicopters and planes and bulldozers in the distance. At first he’d tried using the radio for company but there was something strange about the voices, something between the words which worried him. The children didn’t seem to mind, in fact they’d stared intently at the speaker, their eyes wide and their lips moving soundlessly.

The radio had gone into the trash. The television too.

Three weeks had passed and the city had swelled with uniforms and machines and tent cities. Seth and the children had wandered through the desolate streets, past work crews digging through rubble and trucks laden with corpses, and had stood in Frank Kitts Park looking up at the twisted green figure on the top of Mount Victoria. It was sad somehow, the way the giant limbs twisted into the ground and one arm reached up toward the sky. Seth’s eyes had begun to water as he tried to focus on the creature and he had to blink, to look away. Out in the harbour police boats surrounded the crumbling spires that jutted up out of the sea. Seth had turned his back on the ocean, on the mountain, and stared at the heart of the ruined city, taking comfort from the illusion that something as innocent and simple as an earthquake or bomb had wrought the destruction. Something familiar, something safe.

More time, more frantic activity, and then the ceremony. The dawn service for the victims of The Event.

Seth stood quietly on the stairs of the National War Memorial, the Carillon tower stretching up above him. There were cameras and pink faced people and politicians crowded onto the steps but somehow he’d managed to push through to the front of the crowd, his two silent children forging a path ahead of him. People seemed to instinctively shy away from the children, from Seth too. It wasn’t hard to find a space.

“Ladies and gentlemen, we are gathered here today to pay our respects to the men, women and children whose lives were tragically cut short…”

The words washed over Seth without stirring a response. He’d come because it was expected, because he and the children were survivors, because this was supposedly for them. He’d come because he hoped to leave some measure of his guilt behind on the steps of the War Memorial. He’d come so that he could look into the faces of other survivors and see if his own emptiness was echoed in their eyes.

“…terrible, inexplicable events of that night…”

Seth flexed the fingers of his left arm and glanced down. The skin of his hand was smooth, pale, almost translucent. He’d been frightened enough when he’d woken up in the bucket fountain with the rapidly decomposing, naked corpses of Mark and the fish woman. When he’d realised that the gun he’d used to kill them was nowhere to be found, that the torn, shredded flesh of his left arm where Mark had bitten him had closed over and was almost healed, and that the shattered bones beneath no longer hurt he’d closed his eyes and tried to disappear. He knew that the blood and pus and filth of the fountain would have swallowed him if the children hadn’t come back.

He reached up with his good hand and ruffled the boy’s hair. Alex, that was what the girl had called him. Wherever they’d been, whatever they’d seen above the clouds, they’d come back and found him and pulled him out of the fountain. They’d dragged him up into the hills and waited patiently for him to come back from whatever place inside himself he’d gone away to, and when he was back they’d let him take care of them.

It was good to have family.

The service droned on and Seth watched the crowd. It was obvious who’d been in the thick of the horror and who’d been safely distanced. The pity and disbelief were obvious too. When the sun rose and the shape on Mount Vic was silhouetted by the dawn Seth was surprised to find himself smiling.

The service ended and the crowd dissipated, journalists pouncing on politicians and survivors, civilians retreating to the safety of the suburbs, military personnel returning to their duties. Seth and the children remained on the steps of the War Memorial, standing silently and watching the people go. They were in no hurry. They had nowhere to be.

“Seth?”

The voice was unfamiliar. Hell, after the silence of the past few weeks even the name felt unfamiliar. Seth turned and saw a smooth skinned, dark haired woman wearing a black jacket and skirt, low heels and sunglasses. Behind her stood a tall, broad-shouldered Maori man in a sombre suit. He wore sunglasses too.

“Seth, it’s good to see you,” the woman said, extending a hand.

Seth felt the skin of his left arm convulse and the blood drained from his face. Something cold crept into the pit of his stomach. He thought he had forgotten the taste of fear.

“Who, who are you?” he asked, ignoring the proffered hand.

“People who want to help,” the woman said with a smile. Her teeth were worryingly sharp. “People who know a lot about you.”

“Friends of Mark,” the man behind her said, raising his eyebrows slightly and rocking his head back.

Seth’s eyes darted from the two figures in front of him to the stairs behind him. He could run, but what about the children? Would they follow, or would they stand there and wait for whatever it was these people wanted to do, uncomprehending, blissfully unafraid, and doomed.

“Mark’s dead,” Seth said slowly, pulling the children closer with his good arm.

“We know,” said the woman deliberately, raising a hand and pointing a finger to her temple, thumb raised like a gun. “Dead.”

“We know,” echoed the man, his lips pulling back from his teeth in something between a smile and a sneer.

“And you’ve been touched,” the woman said, leaning closer and reaching out for Seth’s arm.

He found himself unable to resist and raised his left arm, held it out. The translucent skin, shot through with blue veins, was strikingly like the woman’s as she took his hand in hers, caressed it gently.

“We’re starting something. For orphans,” she pointed with a subtle nod of her head towards Mount Victoria. “There aren’t many of us, but we have big plans.”

Seth tried to pull his hand away but the muscles refused to move. He could feel the coldness of alien tissue in his arm, could feel it whispering to this woman. He could feel her whispering back to him, up through the arm and into his mind.

“I can’t, I don’t…” he began, but the woman lowered her glasses with her free hand and stared into his eyes. A tide moved in the depths of those eyes, a tide he could not resist. “I…”

Abruptly the woman screamed. Alex had raised a curious finger and touched the back of her hand. Seth felt the shock of it through her palm like a physical blow and staggered back, his arm throbbing. The woman had fallen back into the arms of her companion, her sunglasses clattering to the ground, and the two of them shared a worried glance. Seth felt his arm burn for a moment as the girl leaned down and took his hand. Her face was calm, blank, and as the burning sensation in his alien skin subsided Seth felt a serene numbness flowing into his arm. The boy, Alex, was slowly walking down the steps, one hand outstretched. The woman and the man backed away as he came, their mouths drawn tight and their movements nervous, frightened. At the base of the stairs they turned and ran.

Seth cradled his left hand in his right, the girl’s small fingers still wrapped around it. As he sat dazed on the War Memorial stairs, looking out at the devastation of the city, the girl stood beside him and held his hand, ran her fingers through his hair. The boy, Alex, returned and sat beside him. In silence they watched over him as his shoulders shook and the early morning sun warmed his tears.

The kids didn’t talk and that was OK. They barely blinked but he could ignore that. They would spend hours staring at the ocean from the safety of the hills, and that was something he shared with them. When it grew dark and the panic started rising inside him Seth could usher the children back into his hilltop apartment, switch on every light, huddle close with them and listen to the sounds of helicopters and planes and bulldozers in the distance. At first he’d tried using the radio for company but there was something strange about the voices, something between the words which worried him. The children didn’t seem to mind, in fact they’d stared intently at the speaker, their eyes wide and their lips moving soundlessly.

The radio had gone into the trash. The television too.

Three weeks had passed and the city had swelled with uniforms and machines and tent cities. Seth and the children had wandered through the desolate streets, past work crews digging through rubble and trucks laden with corpses, and had stood in Frank Kitts Park looking up at the twisted green figure on the top of Mount Victoria. It was sad somehow, the way the giant limbs twisted into the ground and one arm reached up toward the sky. Seth’s eyes had begun to water as he tried to focus on the creature and he had to blink, to look away. Out in the harbour police boats surrounded the crumbling spires that jutted up out of the sea. Seth had turned his back on the ocean, on the mountain, and stared at the heart of the ruined city, taking comfort from the illusion that something as innocent and simple as an earthquake or bomb had wrought the destruction. Something familiar, something safe.

More time, more frantic activity, and then the ceremony. The dawn service for the victims of The Event.

Seth stood quietly on the stairs of the National War Memorial, the Carillon tower stretching up above him. There were cameras and pink faced people and politicians crowded onto the steps but somehow he’d managed to push through to the front of the crowd, his two silent children forging a path ahead of him. People seemed to instinctively shy away from the children, from Seth too. It wasn’t hard to find a space.

“Ladies and gentlemen, we are gathered here today to pay our respects to the men, women and children whose lives were tragically cut short…”

The words washed over Seth without stirring a response. He’d come because it was expected, because he and the children were survivors, because this was supposedly for them. He’d come because he hoped to leave some measure of his guilt behind on the steps of the War Memorial. He’d come so that he could look into the faces of other survivors and see if his own emptiness was echoed in their eyes.

“…terrible, inexplicable events of that night…”

Seth flexed the fingers of his left arm and glanced down. The skin of his hand was smooth, pale, almost translucent. He’d been frightened enough when he’d woken up in the bucket fountain with the rapidly decomposing, naked corpses of Mark and the fish woman. When he’d realised that the gun he’d used to kill them was nowhere to be found, that the torn, shredded flesh of his left arm where Mark had bitten him had closed over and was almost healed, and that the shattered bones beneath no longer hurt he’d closed his eyes and tried to disappear. He knew that the blood and pus and filth of the fountain would have swallowed him if the children hadn’t come back.

He reached up with his good hand and ruffled the boy’s hair. Alex, that was what the girl had called him. Wherever they’d been, whatever they’d seen above the clouds, they’d come back and found him and pulled him out of the fountain. They’d dragged him up into the hills and waited patiently for him to come back from whatever place inside himself he’d gone away to, and when he was back they’d let him take care of them.

It was good to have family.

The service droned on and Seth watched the crowd. It was obvious who’d been in the thick of the horror and who’d been safely distanced. The pity and disbelief were obvious too. When the sun rose and the shape on Mount Vic was silhouetted by the dawn Seth was surprised to find himself smiling.

The service ended and the crowd dissipated, journalists pouncing on politicians and survivors, civilians retreating to the safety of the suburbs, military personnel returning to their duties. Seth and the children remained on the steps of the War Memorial, standing silently and watching the people go. They were in no hurry. They had nowhere to be.

“Seth?”

The voice was unfamiliar. Hell, after the silence of the past few weeks even the name felt unfamiliar. Seth turned and saw a smooth skinned, dark haired woman wearing a black jacket and skirt, low heels and sunglasses. Behind her stood a tall, broad-shouldered Maori man in a sombre suit. He wore sunglasses too.

“Seth, it’s good to see you,” the woman said, extending a hand.

Seth felt the skin of his left arm convulse and the blood drained from his face. Something cold crept into the pit of his stomach. He thought he had forgotten the taste of fear.

“Who, who are you?” he asked, ignoring the proffered hand.

“People who want to help,” the woman said with a smile. Her teeth were worryingly sharp. “People who know a lot about you.”

“Friends of Mark,” the man behind her said, raising his eyebrows slightly and rocking his head back.

Seth’s eyes darted from the two figures in front of him to the stairs behind him. He could run, but what about the children? Would they follow, or would they stand there and wait for whatever it was these people wanted to do, uncomprehending, blissfully unafraid, and doomed.

“Mark’s dead,” Seth said slowly, pulling the children closer with his good arm.

“We know,” said the woman deliberately, raising a hand and pointing a finger to her temple, thumb raised like a gun. “Dead.”

“We know,” echoed the man, his lips pulling back from his teeth in something between a smile and a sneer.

“And you’ve been touched,” the woman said, leaning closer and reaching out for Seth’s arm.

He found himself unable to resist and raised his left arm, held it out. The translucent skin, shot through with blue veins, was strikingly like the woman’s as she took his hand in hers, caressed it gently.

“We’re starting something. For orphans,” she pointed with a subtle nod of her head towards Mount Victoria. “There aren’t many of us, but we have big plans.”

Seth tried to pull his hand away but the muscles refused to move. He could feel the coldness of alien tissue in his arm, could feel it whispering to this woman. He could feel her whispering back to him, up through the arm and into his mind.

“I can’t, I don’t…” he began, but the woman lowered her glasses with her free hand and stared into his eyes. A tide moved in the depths of those eyes, a tide he could not resist. “I…”

Abruptly the woman screamed. Alex had raised a curious finger and touched the back of her hand. Seth felt the shock of it through her palm like a physical blow and staggered back, his arm throbbing. The woman had fallen back into the arms of her companion, her sunglasses clattering to the ground, and the two of them shared a worried glance. Seth felt his arm burn for a moment as the girl leaned down and took his hand. Her face was calm, blank, and as the burning sensation in his alien skin subsided Seth felt a serene numbness flowing into his arm. The boy, Alex, was slowly walking down the steps, one hand outstretched. The woman and the man backed away as he came, their mouths drawn tight and their movements nervous, frightened. At the base of the stairs they turned and ran.

Seth cradled his left hand in his right, the girl’s small fingers still wrapped around it. As he sat dazed on the War Memorial stairs, looking out at the devastation of the city, the girl stood beside him and held his hand, ran her fingers through his hair. The boy, Alex, returned and sat beside him. In silence they watched over him as his shoulders shook and the early morning sun warmed his tears.

Wednesday, October 28, 2009

Part Five - Adam

Adam had been involved in five solid days of clean up, and he was well and truly over it. He and Richard had spent much of the first day digging other people out of wreckage.

Right at sundown, when Adam had felt his heart speed up in fear that the weirdness was about to come back, there was instead a blessed noise. A siren. An ambulance. Adam turned, tears in his eyes, to look in the direction it was coming from.

Richard and Adam received medical attention. They were given water and food and then told that they were alright and turned back out into the night. Adam understood, there were plenty of people who were worse off than them. People who had lost limbs or their minds in what had happened.

Each day after that was just as hard, but Adam and Richard got into a rhythm working alongside each other. Digging people up and moving rubble into semi-organised mounds. Together with about eight other people they got the road clear so that emergency vehicles could get through. They scrounged food from the shops, the windows were all smashed and the shop owners nowhere to be found. The ambulance came round every night to check on them but their supplies ran out quickly.

Adam went to check on his work one morning and found the whole building had been flattened.

No more job.

They could have left on one of the buses. People were being shipped out of town, up to camps on Kapiti coast or further but Adam didn’t see the point of sitting around with a lot of homeless people. On the fifth day the army trucks arrived and Adam’s cleanup crew suddenly had a much easier job. The soldiers were well organised, energetic and they’d been given a brief.

The fifth day closed with another spectacular sunset.

‘It’s all the dust from the destruction,’ Richard said, sitting next to Adam on the hood of the abandoned 4X4 he used to sleep in. ‘You know, like when a volcano goes off? All the ash stays in the sky for months.’

Adam didn’t like looking at the sky anymore, but his eyes were still drawn to the reds and purples at sundown.

‘But it wasn’t a volcano,’ Adam said.

‘No,’ Richard said. ‘I didn’t see exactly what it was...’ he looked at Adam sidelong. This was the 17th time he’d gone digging for information that Adam didn’t want to give, but today felt like the end of something. If the military were taking over the clean up then that left Adam to do his own thing. He felt generous.

‘You ever see Godzilla?’ Adam said, leaning back on his elbows.

Richard nodded, ‘hoards of screaming Japanese businessmen? Huge robot come to fight it off?’

‘S’right, except that it was hoards of Wellingtonians and we didn’t have a giant robot. We had whatever it was that broke the sky.’

They were both silent for a moment, trying not to look up. ‘Giant lizard?’ Richard said, eventually. He sounded like he was making a joke, like he didn’t want to believe it. But the evidence was all around them.

‘I didn’t see it that clearly, but it looked more like a huge guy. Not a lizard, and the feet were almost human. I know it came from the sea though.’

More silence. Adam concentrated on taking deep breaths. Every time he thought about the sea he had to fight off a panic attack. That voice in his head was still telling him to get away from the ocean. Whatever it was had stopped for now, he knew that. He’d seen the frozen tentacles, the way they looked like church spires, and the ocean had stopped trying to get uphill. But his instinct was still to get away, his unconscious knew something he didn’t.

That night he had the dream again. There was a girl, a princess, she was locked in a castle, strapped to a hospital gurney. He was supposed to save her, so he went in and he had a big bit of broken building for a sword. The girl was beautiful, he was heroic. But the dream always ended the same way. When he released her from her prison she transformed, her gorgeous face transforming into a hideous monster and her body swelling to impossible size. He woke up in a cold sweat, the pre-dawn light making his face look pale and sick in the rear view mirror.

Adam turned on his phone. He’d switched it off to preserve the battery once he’d found Richard. The network had been screwed, but he held out hope that the money grabbing phone companies would work to resurrect it.

He dialled the number he’d tried every day and on this day, this magical morning he was rewarded. A ringing noise. It rang for a long time, but then he was calling pretty early. His stomach rumbled, complaining about how little food he’d given it.

‘Hello?’ a voice, someone had picked up. He’d reached the outside world.

‘Mum?’ Adam said, he didn’t mean to get emotional but his voice broke as he said it. He hadn’t dared to hope that he’d ever hear her voice again.

‘Oh my God, Adam is that you?’

‘Yes,’ it was all he could manage. He was actually crying, tears were getting on his phone.

‘We had no idea if you were alive, oh my God. Are you alright? Are you in one of those camps?’

‘No, no Mum. I’m in Wellington still. Look, I was thinking of leaving, coming to see you.’

‘Of course, you have to.’

‘My house, all my stuff is gone. I’ll have to-’ emotions again, he hadn’t acknowledged the loss of all his stuff. His clothes, his DVDs.

‘Ssssh, honey, it’s alright. It will all be alright.’

‘I don’t know how to get to you but...’

‘They have the airport operational again, it’s just for military use and evacuation they said on the TV.’

‘Evacuation, right.’

Richard didn’t want to leave. He said he had too much to stay for, a bar, which Adam thought was probably long smashed, and some girl. Adam thought briefly of Gretchen, wondered if she’d survived. Decided she wasn’t worth it.

Adam and Richard’s goodbye was surprisingly emotional. They’d come to depend on each other through the madness and Adam tried a couple more times to convince him to come along. They embraced for longer than was OK for a red blooded kiwi male and if there were any tears shed, well, they weren’t going to make a fuss about it.

It took Adam the whole day to make his way through town to the airport. It would have been quicker if he’d taken the way around the bays, but he felt like he’d be too exposed on the windy road. Instead he made his way through the destruction to the Mt Vic tunnel, miraculously still standing, but full of crashed cars. It looked to Adam as if motorist after motorist had decided that the crush of cars could be got through if they just accelerated hard enough. Idiots.

He climbed over the hill instead.

The airport was a hive of activity, police cars and army trucks and other trucks, shipping supplies out of the planes and into the ruined city. At the taxi stand for arriving passengers there was a rag tag line of people. A man with a bright yellow reflector vest had a clipboard and was taking names.

‘Is this where you register for a plane?’ Adam asked.

‘Yep, we’re flying people to Palmerston North. You got someone to meet you? ‘

‘Yeah, my parents. They live in Hastings. I’ll give them a call and get them to drive down.’

The man nodded and took his name and eventual destination. 'We might be able to get you closer. I'll let you know when I get the charter schedules.'

The other people in the line looked worn down. Adam imagined he looked the same. He had noticed that he had more muscle definition that morning when he was changing his clothes. Day after day of hard labour and little food will do that, he mused.

Once he was actually on the plane, a crappy little passenger train fit for 50 or so passengers. They had to wait a couple of hours on the tarmac for more people to arrive. Adam stared out the window at the hills. He knew he would never return, and although it made him sad in the pit of his stomach, he was mostly very happy to be getting away.

He was going to stop a while with his parents, long enough to set their minds at ease before he moved away. Somewhere far from the ocean. Like the Australian desert maybe, or middle America. His parents had money, they’d pay for a one way ticket. Nothing could get to him if he knew there was only land outside his front door.

As the plane took off, finally, Adam watched Wellington get smaller and smaller. He wouldn’t come back. He thought instead of the future. It was wide open, he’d never felt such freedom. He certainly wouldn’t get another call centre job. He sighed and sat back, closing his eyes as the plane reached the cloud cover.

His future was wide open and maybe, with the right medication, he could get rid of the dreams.

Right at sundown, when Adam had felt his heart speed up in fear that the weirdness was about to come back, there was instead a blessed noise. A siren. An ambulance. Adam turned, tears in his eyes, to look in the direction it was coming from.

Richard and Adam received medical attention. They were given water and food and then told that they were alright and turned back out into the night. Adam understood, there were plenty of people who were worse off than them. People who had lost limbs or their minds in what had happened.

Each day after that was just as hard, but Adam and Richard got into a rhythm working alongside each other. Digging people up and moving rubble into semi-organised mounds. Together with about eight other people they got the road clear so that emergency vehicles could get through. They scrounged food from the shops, the windows were all smashed and the shop owners nowhere to be found. The ambulance came round every night to check on them but their supplies ran out quickly.

Adam went to check on his work one morning and found the whole building had been flattened.

No more job.

They could have left on one of the buses. People were being shipped out of town, up to camps on Kapiti coast or further but Adam didn’t see the point of sitting around with a lot of homeless people. On the fifth day the army trucks arrived and Adam’s cleanup crew suddenly had a much easier job. The soldiers were well organised, energetic and they’d been given a brief.

The fifth day closed with another spectacular sunset.

‘It’s all the dust from the destruction,’ Richard said, sitting next to Adam on the hood of the abandoned 4X4 he used to sleep in. ‘You know, like when a volcano goes off? All the ash stays in the sky for months.’

Adam didn’t like looking at the sky anymore, but his eyes were still drawn to the reds and purples at sundown.

‘But it wasn’t a volcano,’ Adam said.

‘No,’ Richard said. ‘I didn’t see exactly what it was...’ he looked at Adam sidelong. This was the 17th time he’d gone digging for information that Adam didn’t want to give, but today felt like the end of something. If the military were taking over the clean up then that left Adam to do his own thing. He felt generous.

‘You ever see Godzilla?’ Adam said, leaning back on his elbows.

Richard nodded, ‘hoards of screaming Japanese businessmen? Huge robot come to fight it off?’

‘S’right, except that it was hoards of Wellingtonians and we didn’t have a giant robot. We had whatever it was that broke the sky.’

They were both silent for a moment, trying not to look up. ‘Giant lizard?’ Richard said, eventually. He sounded like he was making a joke, like he didn’t want to believe it. But the evidence was all around them.

‘I didn’t see it that clearly, but it looked more like a huge guy. Not a lizard, and the feet were almost human. I know it came from the sea though.’

More silence. Adam concentrated on taking deep breaths. Every time he thought about the sea he had to fight off a panic attack. That voice in his head was still telling him to get away from the ocean. Whatever it was had stopped for now, he knew that. He’d seen the frozen tentacles, the way they looked like church spires, and the ocean had stopped trying to get uphill. But his instinct was still to get away, his unconscious knew something he didn’t.

That night he had the dream again. There was a girl, a princess, she was locked in a castle, strapped to a hospital gurney. He was supposed to save her, so he went in and he had a big bit of broken building for a sword. The girl was beautiful, he was heroic. But the dream always ended the same way. When he released her from her prison she transformed, her gorgeous face transforming into a hideous monster and her body swelling to impossible size. He woke up in a cold sweat, the pre-dawn light making his face look pale and sick in the rear view mirror.

Adam turned on his phone. He’d switched it off to preserve the battery once he’d found Richard. The network had been screwed, but he held out hope that the money grabbing phone companies would work to resurrect it.

He dialled the number he’d tried every day and on this day, this magical morning he was rewarded. A ringing noise. It rang for a long time, but then he was calling pretty early. His stomach rumbled, complaining about how little food he’d given it.

‘Hello?’ a voice, someone had picked up. He’d reached the outside world.

‘Mum?’ Adam said, he didn’t mean to get emotional but his voice broke as he said it. He hadn’t dared to hope that he’d ever hear her voice again.

‘Oh my God, Adam is that you?’

‘Yes,’ it was all he could manage. He was actually crying, tears were getting on his phone.

‘We had no idea if you were alive, oh my God. Are you alright? Are you in one of those camps?’

‘No, no Mum. I’m in Wellington still. Look, I was thinking of leaving, coming to see you.’

‘Of course, you have to.’

‘My house, all my stuff is gone. I’ll have to-’ emotions again, he hadn’t acknowledged the loss of all his stuff. His clothes, his DVDs.

‘Ssssh, honey, it’s alright. It will all be alright.’

‘I don’t know how to get to you but...’

‘They have the airport operational again, it’s just for military use and evacuation they said on the TV.’

‘Evacuation, right.’

Richard didn’t want to leave. He said he had too much to stay for, a bar, which Adam thought was probably long smashed, and some girl. Adam thought briefly of Gretchen, wondered if she’d survived. Decided she wasn’t worth it.

Adam and Richard’s goodbye was surprisingly emotional. They’d come to depend on each other through the madness and Adam tried a couple more times to convince him to come along. They embraced for longer than was OK for a red blooded kiwi male and if there were any tears shed, well, they weren’t going to make a fuss about it.

It took Adam the whole day to make his way through town to the airport. It would have been quicker if he’d taken the way around the bays, but he felt like he’d be too exposed on the windy road. Instead he made his way through the destruction to the Mt Vic tunnel, miraculously still standing, but full of crashed cars. It looked to Adam as if motorist after motorist had decided that the crush of cars could be got through if they just accelerated hard enough. Idiots.

He climbed over the hill instead.

The airport was a hive of activity, police cars and army trucks and other trucks, shipping supplies out of the planes and into the ruined city. At the taxi stand for arriving passengers there was a rag tag line of people. A man with a bright yellow reflector vest had a clipboard and was taking names.

‘Is this where you register for a plane?’ Adam asked.

‘Yep, we’re flying people to Palmerston North. You got someone to meet you? ‘

‘Yeah, my parents. They live in Hastings. I’ll give them a call and get them to drive down.’

The man nodded and took his name and eventual destination. 'We might be able to get you closer. I'll let you know when I get the charter schedules.'

The other people in the line looked worn down. Adam imagined he looked the same. He had noticed that he had more muscle definition that morning when he was changing his clothes. Day after day of hard labour and little food will do that, he mused.

Once he was actually on the plane, a crappy little passenger train fit for 50 or so passengers. They had to wait a couple of hours on the tarmac for more people to arrive. Adam stared out the window at the hills. He knew he would never return, and although it made him sad in the pit of his stomach, he was mostly very happy to be getting away.

He was going to stop a while with his parents, long enough to set their minds at ease before he moved away. Somewhere far from the ocean. Like the Australian desert maybe, or middle America. His parents had money, they’d pay for a one way ticket. Nothing could get to him if he knew there was only land outside his front door.

As the plane took off, finally, Adam watched Wellington get smaller and smaller. He wouldn’t come back. He thought instead of the future. It was wide open, he’d never felt such freedom. He certainly wouldn’t get another call centre job. He sighed and sat back, closing his eyes as the plane reached the cloud cover.

His future was wide open and maybe, with the right medication, he could get rid of the dreams.

Saturday, October 10, 2009

Part Five - Michelle

Michelle’s arm hurt. It was throbbing even more than it had been when she had first woken up. The pain was almost unbearable. She considered pushing the button for the nurse but what was the point? All the nurses and doctors were run off their feet in the overcrowded hospital. She’d have to wait for ages to get a response. Besides, it wasn’t like the painkillers they gave her did any good anyway.

She looked around the hospital room. It wasn’t a small room, probably supposed to have four beds in it but they’d wheeled in another five beds and they were all squashed up together, the stainless steel bars of one bed pressing up against the next.

Michelle’s bed was one of the original ones; it was meant to be there. She knew that because the pale green curtains could be pulled around her bed. A teenage girl had been wheeled in not that long ago and a large middle-aged lady, presumably her mother, had been fussing over her. The lady had looked at Michelle with a frightened look of pity and had pulled the curtains closed around her bed.

“I’ve give you a little privacy, dear,” she had said in a kind voice as though she was looking after Michelle rather than shielding her daughter from the gruesome sight.

Still it had made Michelle realise her bed belonged there. It had its rightful, permanent position. It was comforting, like a small recognition that she was worse off than the other patients.

When a nurse had come to check on her later she had pulled the curtains open and hadn’t bothered to close them again when she left. After everything she’d probably seen, Michelle supposed she didn’t look that bad or maybe it was just that after what had happened to Wellington she didn’t see the point in trying to protect anyone.

Michelle wondered where they had put all the chairs and small tables that were usually pushed up by the bedsides. It wasn’t like she’d had any visitors or flowers yet anyway. It was all too soon for that. Most of the roads had been damaged or were cordoned off for emergency vehicles only. Her parents probably hadn’t even heard about what had happened to her yet. They wouldn’t be able to make it down to see her yet even if they had been notified.

It was strange how she wanted her parents but didn’t want them to see her like this at the same time. Maybe it would have been easier on them, and on her, if she had died.

She choked back a bitter sob when she remembered what the doctor had said when she first came round in the hospital - ‘lucky to have survived’. She wasn’t lucky and she wasn’t sure she had survived either.

He’d had rambled on about prosthetic arms and skin grafts to repair the torn gashes on her face. He’d had said that it would take time to see if her left leg could be saved, to see if there was enough muscle and nerve tissue. He’d told her that it was amazing that she hadn’t died from the shock and blood loss.

He’d had said that word again. He’d said that she was lucky to be alive.

Michelle looked around the room again. She wondered what time it was. The artificial hospital lights and the grey mist of the aftermath that hung over the city outside the square window gave her no clue. It could have been morning or late afternoon. What did it matter anyway?

There was a new guy in the bed opposite her. The teenage girl and her ‘considerate’ mother had left. It was the usual procedure. They were bandaged up, given an IV drip for the dehydration and after a couple of hours of observation (not that anyone seemed to have the time to watch them) they were moved on if nothing unusual had happened. How many of them had cycled through the room while Michelle had been there?

He made her uncomfortable, the new guy. His arm was plastered up in a pristine white cast and he had the usual cuts and bruises. Nothing serious. She looked over him. Longish brown hair, goatee beard, torn and bloodied clothing; the nervous look in his eyes as they constantly darted around the room was the only indication that something much worse than a drunken fall or minor accident had happened to him.

She envied his plaster-covered arm. She had broken her arm when she was seven. At school all the kids had wanted to write their names on it and decorate it with colourful pictures and funny messages. Even the kids that didn’t like her very much had wanted to sign it. Michelle had felt special every time she down looked down at the cast covered with the attentions of so many. She had even kept the cast after her arm had healed.

She doubted that anyone would volunteer to sign a prosthetic arm. They’d all think it was creepy if she ever suggested it.

The heady pull of morphine urged her to close her eyes but as soon as her eyelids fell they leapt back out at her. Snarling mouths and pointy teeth, they lunged and she fell. With her eyes closed even for a second she could feel the teeth tearing at her arm and leg, the flesh ripping away with a shocking, painful heat.

She had to keep her eyes open. She had to try to forget.

It was easier when she focussed on the hopeful possibilities. There was still the mystery of who had saved her, who had got her away from their terrible creatures. She pictured the tall hero, beating his way through the mob of eyeless ones and pulling the savage eaters off her. He moved in slow motion and bent down to pick up her bloodied and unconscious body. Who knew how far he had to carry her before they reached safety? Sometimes he was played by Clive Owen, other times Eric Bana but he always stayed with her until he knew she was safe.

It was a troubling mystery as to where the hero was now. Had he collapsed from exhaustion and injuries he suffered during her rescue? Could he be in the hospital now, being treated in another room? Maybe he had left to go and save others in the fallen city. Maybe he just thought it would be better this way.

Michelle clung to the hope that he would return. He’d show up with a bouquet of flowers, anxious to see that she’d survived. He’d stand by her and keep her spirits up as she recovered. He’d give her a reason to keep living.

Of course there were other scenarios that Michelle played through in her mind. There was always the possibility of the handsome doctor. It wouldn’t happen straight away of course. The medical staff were too exhausted and distracted at the moment but in a couple of days when she started to heal and the hospital wasn’t bursting with the constant flux of patients, that’s when they would meet. He’d look past her horrific injuries and see the beautiful girl beneath. After all, something had to come out of all this horror. Every movie she’d ever watched confirmed it. Nice people didn’t suffer terrible life-destroying losses without then gaining something far more valuable through it.

She held on to her vision and finally gave into the drug-induced slumber.